Newsroom AI Insight

Why the future of journalism is Modular

Created on: July 11, 2022

This article reflects on the process and outcomes of my Clwstwr-funded research & development looking at “News Storytelling through Modular Journalism”.

I believe very deeply in the power of collaboration to help us solve the existential problems facing journalism and wider society, and this work was largely done in partnership with newsrooms from across the EMEA region, as part of the JournalismAI Collab Challenges facilitated by the Polis think-tank at the LSE. I am therefore happy to personally own any criticism of this article, but any credit should be shared by the teams from Deutsche Welle, Il Sole 24 Ore and Maharat – led by Layal Bahnam, Pier Paolo Bozzano, Marina Caporlingua, Ruth Kühn, and Nada Saab. Thanks too to Alan Renwick and Gary Rogers of Radar AI, who contributed fundamental insights and expertise to the initial research, to the BBC’s David Caswell who has informed, inspired and supported this work from the very beginning. This work would not have been possible without funding from Clwstwr, but particularly the wraparound support provided by Professor Justin Lewis and Sally Griffith.

My research into News Storytelling through Modular Journalism has demonstrated the success of approaching journalistic storytelling differently, so this article follows many of the principles that I’ve identified. The aim here is to give the full context to the story of the R&D in a linear storytelling format, providing you – the reader and user – with the information you need to judge whether the work might help you understand the world better and make your experience of it better.

WHAT HAPPENED?

Across 2019-20, I carried out R&D into news storytelling which identified a set of principles I call, “The 7 Building Blocks of Reflective Journalism”. These start with Narrative, with a key finding being that linear storytelling formats are much more effective in driving engagement and understanding than the inverted pyramid style habitually used in journalism.

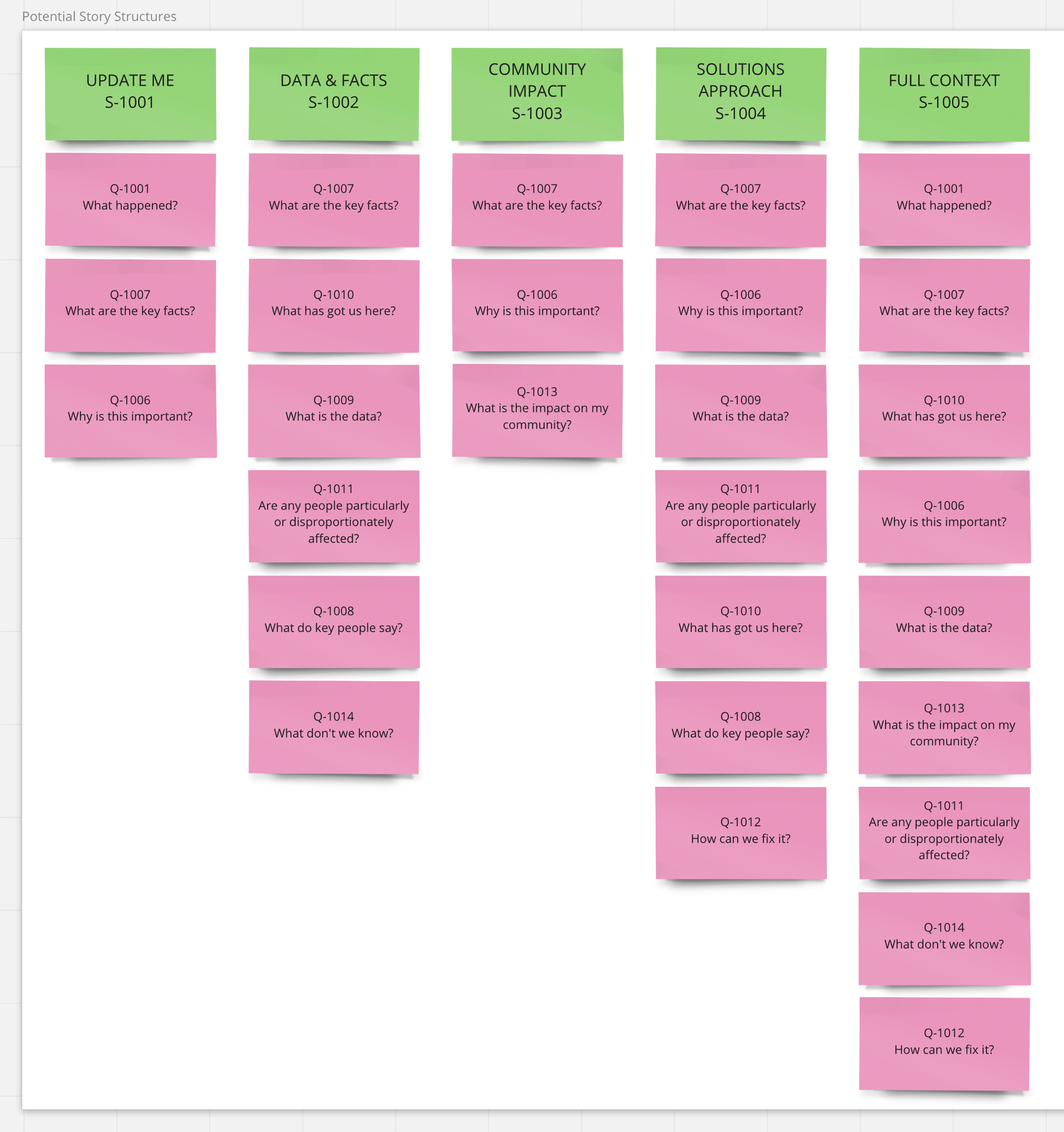

I then extended this research, to look at how we could use those principles in “modular” storytelling formats. The impetus to use new modular storytelling approaches must begin with an understanding that the traditional “one to many” article cannot hope to meet the almost infinitely diverse needs of potential news users. To meet those diverse needs, we need to create a diversity of stories, whilst also acknowledging that we are working in an environment where the journalism workforce is contracting rather than expanding.

One way of doing that is to create multiple, smaller, functional units of news journalism, instead of singular articles. These modules of journalism can then be combined and recombined in a variety of ways (either manually or automatically) to provide stories which meet the needs of a wider range of users.

Identifying what those needs might be, and the linguistic, technical and practical considerations we need to address in order to create this diverse range of stories was the challenge we took on as the initial stage of the JournalismAI Collab Challenges, seeking to define an algebra for news modules. As part of that work, we also created a set of prototypes in a variety of languages, which proved that the algebra and methodology work effectively in storytelling terms.

I then built further prototypes, focusing on one particular story – the Belarus border crisis of late 2021 – and tested these with a demographic cross section of the population to compare their experience of modular stories against their experience of a comparable BBC News story. As you can see, we wrapped the modular prototypes in BBC branding, to remove that variable and enable direct comparison on a level playing field.

This particular story was chosen because it was an issue which people wouldn’t necessarily have a lot of pre-existing knowledge about, and so their responses would not be coloured by previous knowledge. This turned out to be the case, with only around half of respondents being aware of the Belarus border crisis at all. Their average score for how informed they felt about the story was 3 out of 10.

Having said that, given that we also wanted to gauge whether solutions approaches or analysis of the impact on UK communities would be useful to users, the fact that neither of these were particularly clear for this story meant that this perhaps wasn’t the ideal story on which to test those aspects.

It is worth reiterating that this work cannot and should not just focus on formats, because it’s crucial that we also innovate in the underlying journalism. Therefore, we worked hard on avoiding the habits and formulas of journalism and trying to write more clearly, providing useful and/or actionable information in order to help users navigate the world, and thinking about how new editorial approaches might help create different, but better, journalism in the future.

Much of this thinking focused on the key concept of “Orientation” developed alongside the 7 Building Blocks of Reflective Journalism.

“Journalism should help us understand the world, locate us in our environment and enable us to meaningfully interact with it. Journalism should help us form views which are consistent with the needs and interests of our families and our communities.”

The results of the testing comprehensively indicate that modular journalism stories have demonstrable benefits for users. Not only did readers find them significantly more engaging, informative, interesting, useful and even more trustworthy, but respondents expressed strong preferences in favour of having more modular, flexible, tailored journalism in future.

WHAT’S THE DATA?

To assess the effectiveness of the modular journalism approach we’d developed, I tested our prototypes with a cross-section of the population.

I created a survey which first assessed some baseline information on users’ consumption of news. We then asked them to read either a modular journalism prototype (they could choose from mobile or desktop versions) or a comparable BBC News article which was written at the same time. For the reasons discussed above, it’s fair to say that the two presentations do not contain exactly the same or comparable information, because the editorial approach is different, and we included content that I felt would better meet the orientation needs of users. For instance, we included more data and broader contextual information in the modular articles than was present in the BBC news story.

We asked some additional questions to the participants who read the modular articles, to gauge specific reactions to those stories and to try to understand which versions they found most effective and/or were most likely to use if the option were available to them.

For the regular BBC article 356 people started the survey, with 279 people completing it. For the modular article, 367 people started it, with 242 completing it. On the common baseline questions, responses on both surveys very closely mirrored each other. Therefore, where I’ve included results or charts below for illustrative purposes, they may reflect just the responses to one of the surveys, but can be taken to be closely representative of both groups.

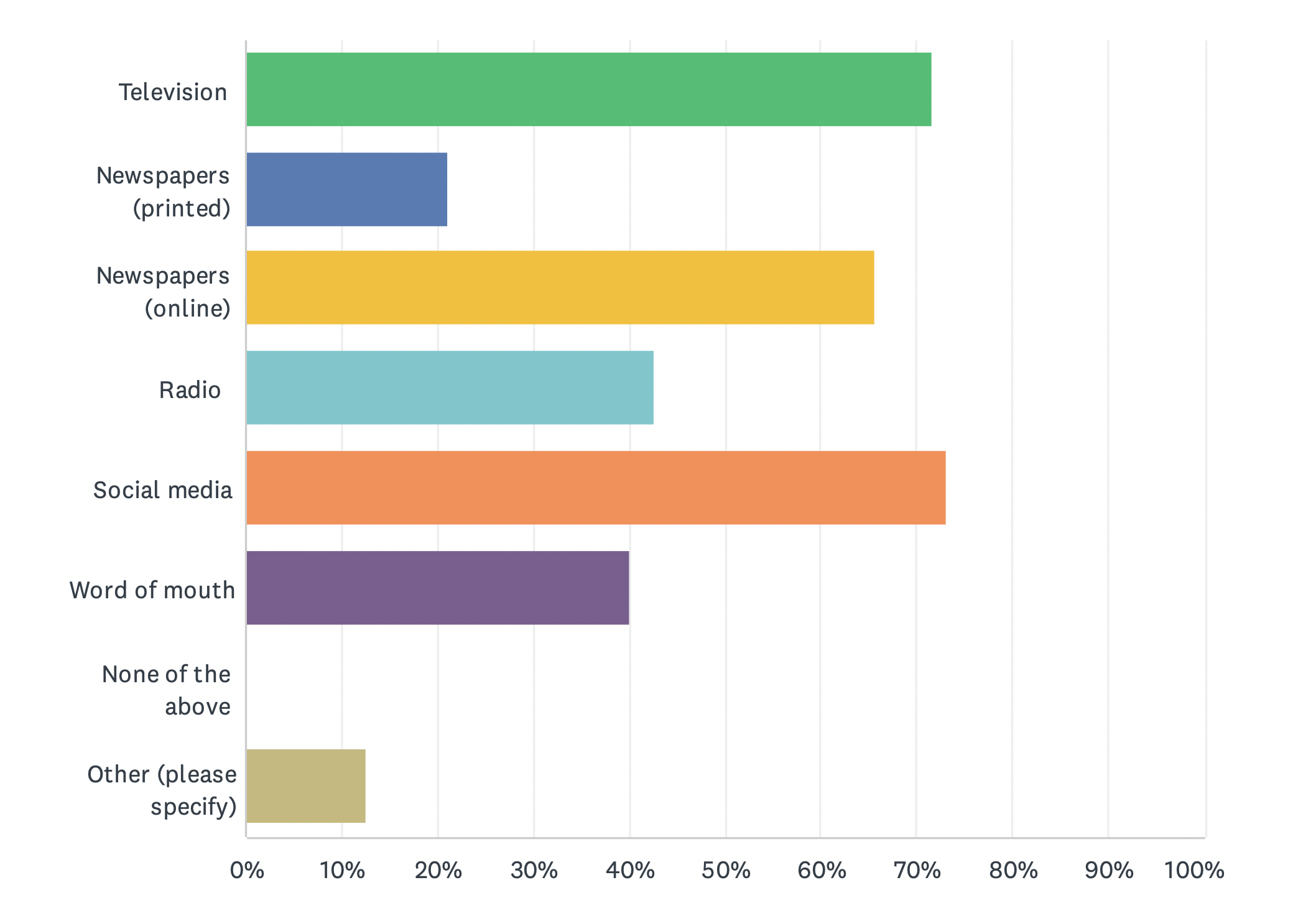

To briefly summarise the baseline information we gathered, respondents engage fairly broadly with news, with approximately 50% spending more than 20 minutes per day reading, watching or listening to news. Respondents generally feel like they’re up to date on news and current affairs – so when asked how well informed they feel, their average rating was 7 out of 10.

Changing patterns of consumption are evident, with social media being the most used source of news, with more than 70% using social media as part of their daily news consumption. Only slightly fewer used TV as a source for news, with online newspapers being the next most popular source. Interestingly, around 40% of respondents get their news via word of mouth, so network effects are clearly important.

Trust is perhaps the crucial issue facing the journalism industry right now, and respondents’ trust in journalism as a whole rated at 5.18 out of 10, with trust in BBC News being slightly higher, at 5.6 out of 10, but still worryingly low.

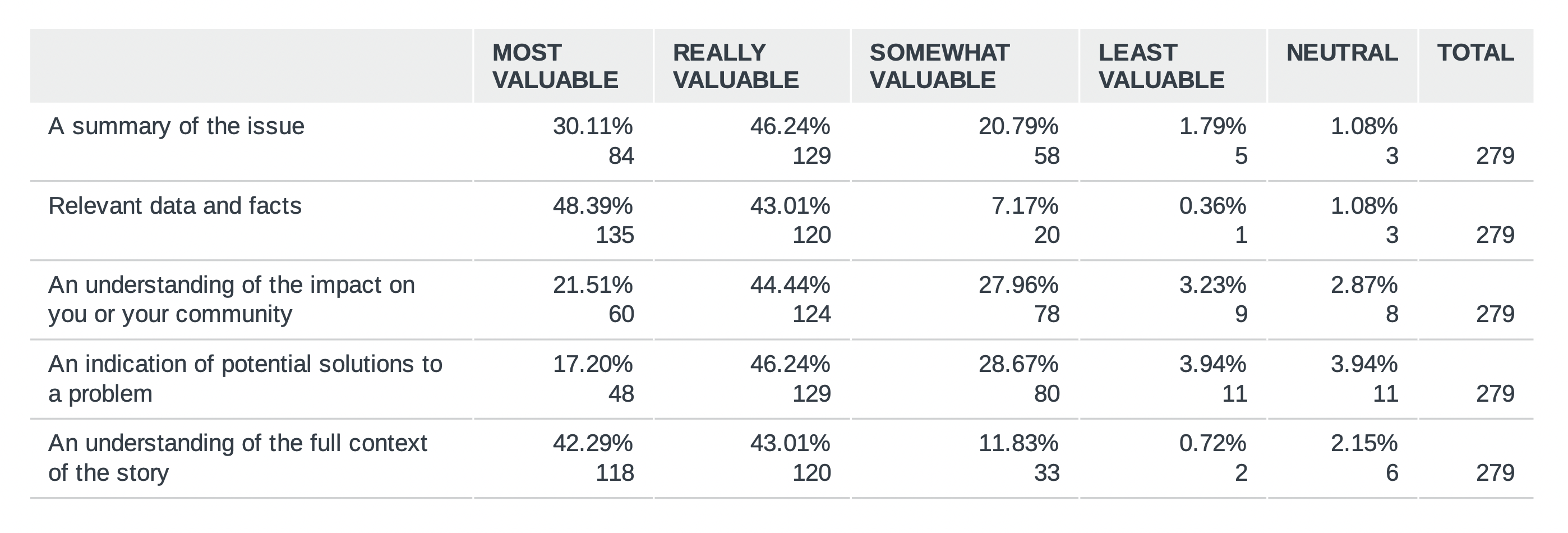

We next asked participants what information is valuable to them when they read a news story. This is useful in understanding what modules users might want to see or use in future.

We can see that there are strong preferences for “Relevant data and facts” and “An understanding of the full context of the story”. In my previous research it was clear that users found the lack of both of these as a weakness of current models of journalism – with a repeatedly expressed demand for greater contextual information. This is also indicated by the fact that a “Summary of the issue” is seen as less valuable than context or data. This feels a significant finding, and reflects what I’ve heard in previous research – that summaries with little contextual information (e.g. Breaking News push alerts) are unhelpful to users hoping to understand a story.

We gave respondents the opportunity to add further insight as to why they made their choices, and there were some rich and useful contributions which will help shape further work:

“I prefer to have as many facts available to me as possible when regarding an important and serious issue. A quick overview is OK, but I much preferred being able to find out why this all started properly and why the president of Belarus was under the microscope.”

“I prefer hard facts and data within my news articles so that I can form my own opinions over interpretation and opinion from dubiously related experts and journalists.”

“I’m disabled and there are days I wouldn’t be able to take in all the facts. On those days shorter, more direct articles are better for me. However, on topics I find important, having access to the full facts is important.”

“I like the opportunity of a quick read alongside the ability to gain extra data and the full context of a news story.”

“I found the community impact the most engaging and relevant to me. I am interested in solutions because it helps me to feel positive and find a way to contribute through my own life.”

“I usually prefer to have objective data and facts and ideally all sides and implications of a global event. I like this particular way to present it, in brief sections that I can choose to read or skip, depending on each particular story, but knowing all the information is there in one place if I need it.”

“For a story like this one which is ongoing, I would initially make most use of the full story as it wasn’t an issue I felt particularly informed about before reading. However afterwards I would prefer the updates and facts from daily events as I feel this would give me a better understanding of the changing situation.”

“I don’t have a lot of time and concentration. So breaking the whole article down into chunks helps. If I had more time and energy I would want to read the full context.”

“If I already know the background of the news story I would just likely read about the current updates and maybe refresh my memory about the context and facts/data.”

The perceived value of solutions approaches, or an understanding of the impact on individuals and their communities, was less pronounced. In truth, that may be because of an imperfect story choice on my part. There were only somewhat indirect impacts from the Belarus border crisis on UK communities at the time, and there was not an obvious route towards a solution. Therefore, this particular article was quite weak on those aspects.

Respondents reflected this in their feedback and so this is likely not a fair test of those elements of the modular story. However, reflecting on the writing of those modules and the survey feedback, in truth it may not be possible to write solutions content which fits well into a modular format. Respondents suggested that the modular option they’d be least likely to consume was the one which analysed the impact on their community. That being said, almost 43% of people would be “very” or “somewhat” likely to use it.

After respondents had read the articles, we asked them to rate how well informed they now felt about the situation which played out on the Belarus border in November 2021.

Respondents who had read the modular version reported an average rating of 6.86 on this question, with respondents who read the BBC News article reporting an average rating of 6.51. It’s worth noting that the BBC News article was 783 words long, which compares very closely with the 793 words used in the discrete modules of the prototype article. Clearly, how informed users feel after reading an article is an important measure of efficacy. Here the modular article does better than the BBC article, but only slightly – around 5% better.

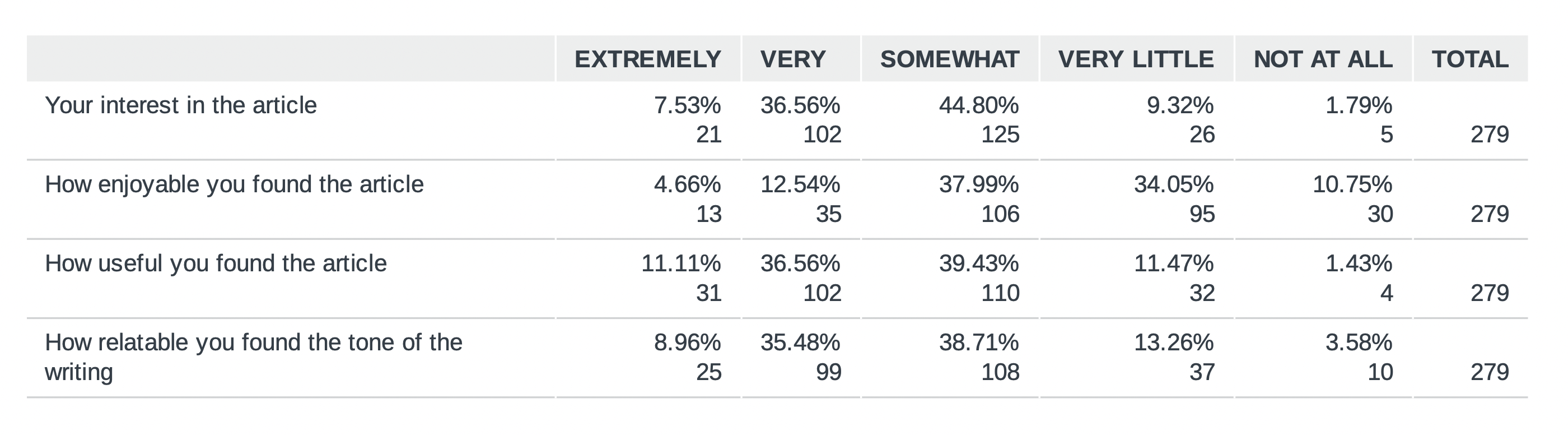

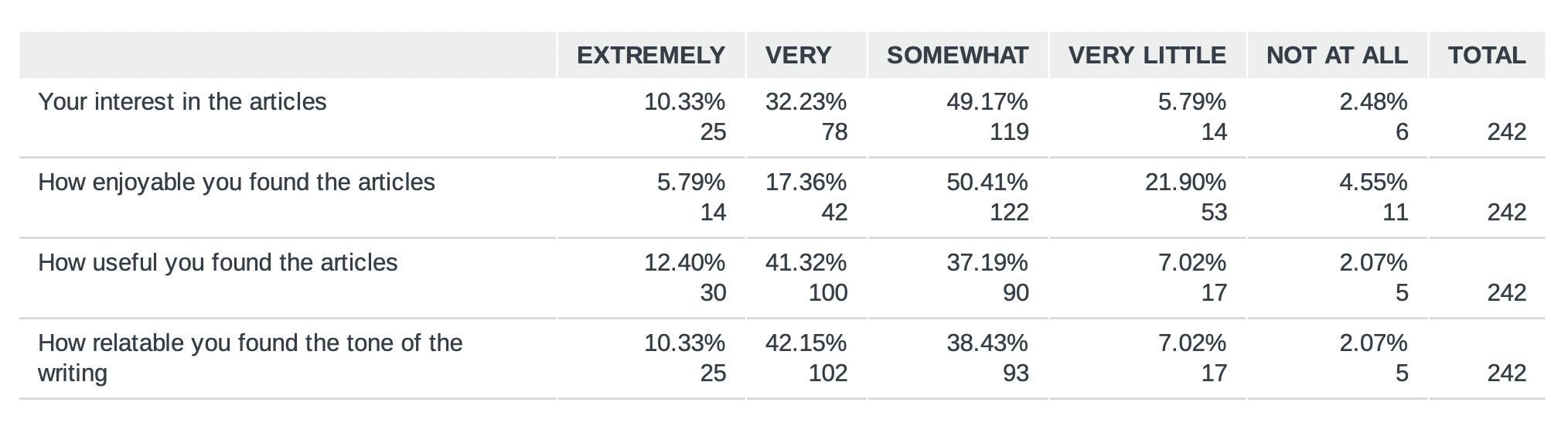

We then asked respondents to rate their interest in the articles and how enjoyable, useful and relatable they found them.

For the BBC News article, responses were as follows:

For the Modular news articles, responses looked like this:

Overall, the modular article is broadly regarded as better than the standard BBC article, although the scale of the difference depends upon how one chooses to compare. For example, if one adds up and compares the “Extremely” and “Very” responses to both articles, the modular article does better on all measures apart from “Interest”. However, more people rate the modular article “Extremely” interesting.

It is also worth reflecting that, in general, we are trying to engage users who currently don’t use news journalism, so it’s also worth looking at the responses at the other end of the scale. Although, by definition, we’re dealing with smaller numbers at this end, we find that double the percentage of respondents find the BBC article not enjoyable at all. If one adds up the “Very little” and “Not at all” responses for both surveys, the modular articles are better regarded than the BBC article on all measures.

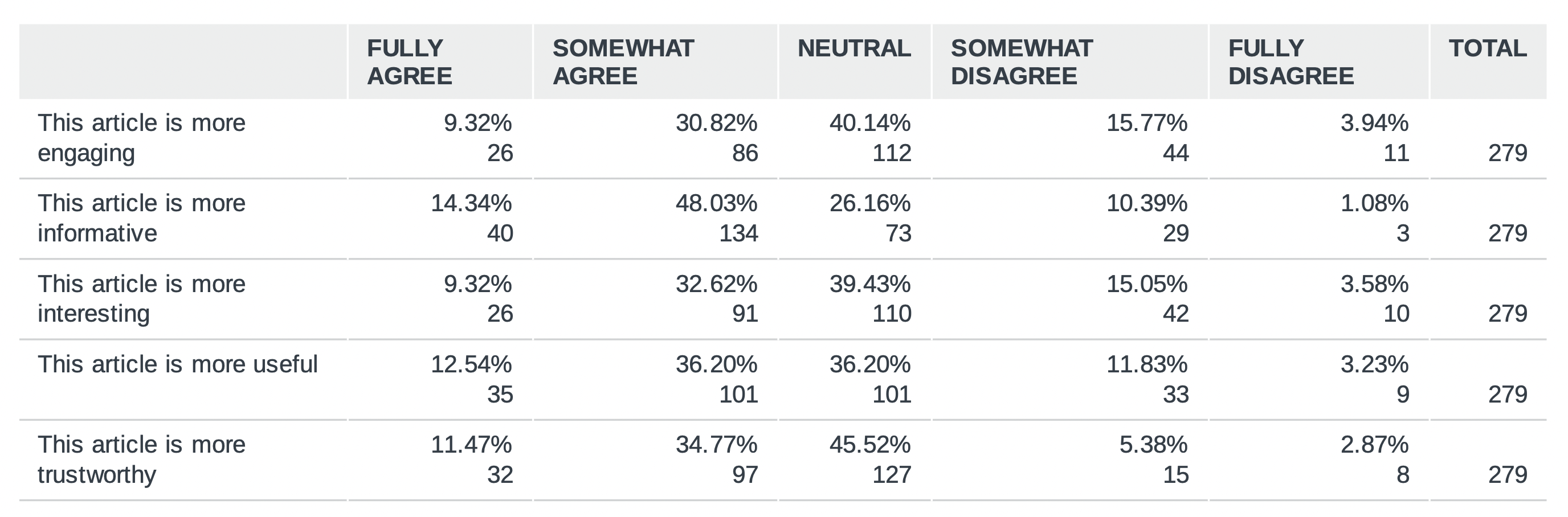

Perhaps the most revealing responses came when we asked respondents if, “comparing the design and content of this news article to others you have read in your own time, to what extent do you agree with the following:

- This article is more engaging

- This article is more informative

- This articles is more interesting

- This article is more useful

- This article is more trustworthy

For the BBC News article:

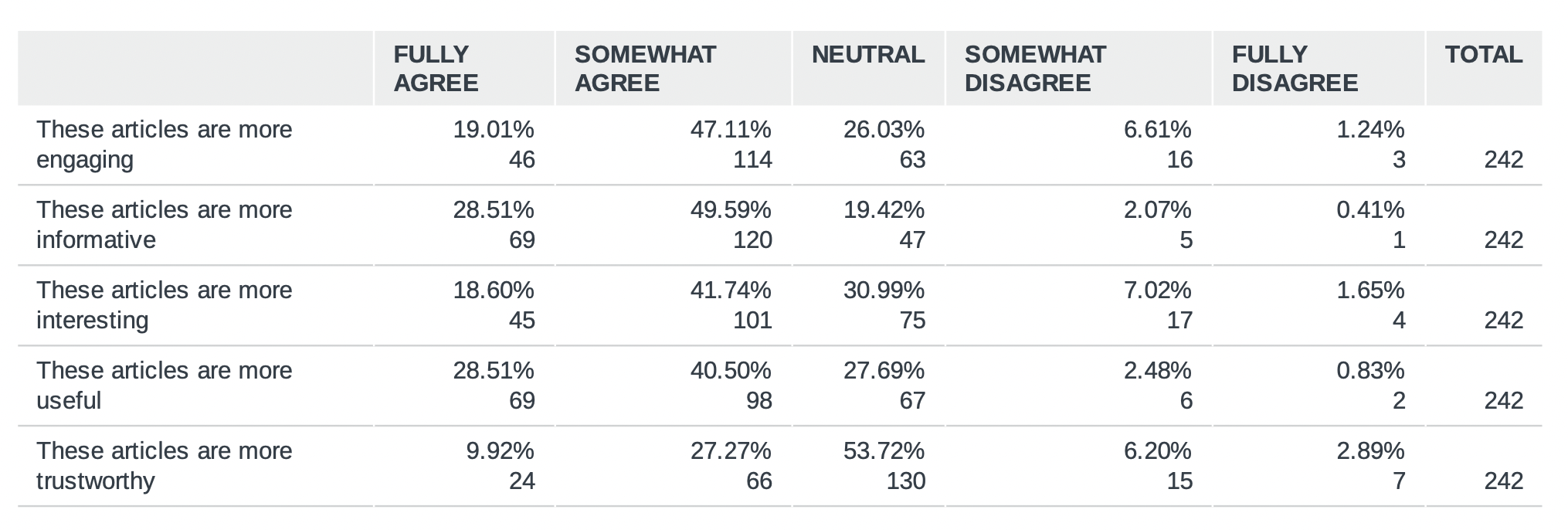

And for the modular news articles:

Here we can see that around twice as many people “Fully agree” that the modular articles are more engaging, informative, interesting and useful than the BBC News article. The BBC News article is, however, better regarded on trust. We don’t know the exact reasons for this, and it’s worth noting that respondents are far more likely to be “neutral” on this. In truth, this was a slightly speculative question, because there wasn’t much in the modular articles that was specifically aimed at inspiring trust. However, given that this is the key problem the journalism industry is facing, it will be important to do more work on creating modular content that does help drive trust. Some of the open-ended feedback to the survey suggested that there were concerns that the “solutions” and “community impact” elements of the modular story felt like journalistic opinion, so this is clearly a risk that needs to be considered. On the other hand, it may be that modules which, for example, take a radical approach to journalistic transparency, might be beneficial.

WHAT ARE THE KEY FACTS?

For me, the key takeaways are:

- The design and content of the modular articles is seen as significantly more engaging, informative, interesting and useful than traditional news articles

- People are most interested in being able to access data and facts, and the full context of a story.

- It may not be possible to effectively include solutions journalism elements into these concise modular forms, if we do proceed with this approach, we will have to consider carefully how this should be done.

- The modular stories don’t inherently have a positive impact on trust – more work needs to be done on this crucial aspect of the work.

- People overwhelmingly appreciated having the option of consuming modular articles in a range of ways. There is demand and enthusiasm for the approach.

WHAT DON’T WE KNOW?

The results of the user testing provide us with valuable insights, but also point to things we don’t yet know, and that I’d want to explore more deeply in future research.

- The respondents’ general level of engagement with news is fairly high. We do however, ultimately hope to better engage people who don’t currently engage with news a great deal. In future research, it may be useful to focus future user-centred design and research on that group.

- It would be useful to understand more deeply what exactly users want from “Full context” and “Data and Facts”, because these are quite wide categories. It will be important to drill down into the precise user needs here.

- Similarly, although there is not a “lack” of interest in the community impact and solutions approaches, it would be useful to understand how much the responses to these elements were driven by the difficulty of illustrating them in the particular Belarus border story, or if there is generally less interest in those modules.

- Whilst I attempted to write the modular stories in clearer, more accessible ways (and this was reflected in respondents seeing them as being written more relatably) I’m keen to do more R&D on how we can embed Content Design principles into journalism, with the aim of making our writing and design much more accessible to all users.

- Initial research has focused on how we might reimagine standard web or app stories but, given changing patterns of consumption, it’s clear that we need to work on how these modular principles might be applied to providing news on social media but also in environments or applications which are still emerging or are yet to come.

- We also need to explore more deeply how we might apply AI and/or Machine Learning to support modular journalism workflows, to enable this journalism to be provided efficiently at scale. We started that work as part of the JournalismAI Collab Challenges, but it became clear that we needed to do a lot of basic editorial work first, in order to have something concrete on which to base further investigation of workflows.

- We don’t have a clear sense from this research what content might inspire trust, but that is something we need to address better. Some of the open-ended feedback pointed to a preference for facts and data, as opposed to journalistic opinion or interpretation of any kind. It may also be that there is more we can do around journalistic transparency here, but we need to take this aspect of the work on more systematically in future.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

These results are important because we urgently need to find new forms of storytelling which engage and inform diverse groups of users, in ways that meet their needs. Here we have initial evidence that people respond well to modular forms of storytelling, and find that more user-focused approaches to the underlying journalism help make it more engaging, informative, interesting and useful.

We also better understand, as a result of this research, people’s preferences for data, facts and context and can now work on understanding these needs better and providing content which meets those needs more effectively.

It’s clear that we need to find new approaches to journalistic storytelling, because the “one to many” approach no longer meets the needs of the wide range of users we want to serve. This is true in the news environments which already exist, but is perhaps even more true in the news environments which are to come. We know that consumers are already getting much of their “news” from social media, and not all of that is from news brands. We therefore need to address how these approaches fit into that world.

While more agile industries are focusing on Web 3.0, much of the journalism world has barely got to grips with Web 2.0 – essentially still just putting newspaper articles online. Modular approaches give us a route to using AI and machine learning to systematically produce more and better journalism at scale.

As just one concrete application, Spotify is already looking at providing users with personalised, automated experiences that might, for example, programme your morning commute. A user might be woken up by their favourite music, before being served a personalised, geolocated news bulletin as they brush their teeth. They might then be offered weather and transport information that tracks their movements and a news podcast that is dynamically configured to match the duration of their journey. Modular journalism is not just useful, but essential if we want to be part of that world, because standard inverted pyramid news articles simply won’t work in a much more personalised, dynamic and non-linear world.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the journalism itself will become more automated, rather that we are able to use the tools available to us to develop new workflows that enable us to better serve the needs of our users. Right now, a typical BBC News workflow is for one person, usually in London, to write one article that is meant to serve the needs of everyone in the world.

I imagine instead, a not very distant modular future in which some journalists might be creating “evergreen” contextual modules, some journalists are working on “on the day” updates and local journalists all over the world could be providing the modules analysing local impacts. When combined into modular presentations of the kind we’ve prototyped here, there is the potential for the journalism to be much more robust, much more locally tailored, much more informative and frankly much more efficient than our current approaches.

The results presented here validate our initial R&D, by proving the success of modular articles in meeting key user needs. However, they also provide important insights into areas such as trust, where we still need to do better.

This is not simply a question of effectiveness when compared against formats which currently exist though, because modular formats are clearly going to be necessary as we look to the future, Web 3.0 and a world where new methods of communication and interaction will be required.

Created on: July 11, 2022

Has this sparked ideas for you?

Do get in touch if you want to pick up on any of these thoughts.

contact